Of a House Dreaming

As our house was being constructed, Owner Builder Magazine, then a familiar sight on News stands, asked me to write the story of the building of our house, because of the innovative way the house was being built. Here is the story, as published by them, in three episodes of that magazine, each a year apart.

This is the story, for us to keep forever, about how we came to be living in this ideal part of the world in a house we shall never leave. It is an idea of a house of glass that is dreamt up on the deck of a sailing boat in the middle of the Pacific, when Ted and I are finishing our sailing circumnavigation of the world. Having been living on our boat for five years, the idea of living inside walls, where you were not joined to the natural world, did not seem alluring.

…………..

We are in the middle of the Pacific, sailing our 14 metre boat between the Galapagos and the Marquesas islands in French Polynesia. It is a 5,500 kilometre voyage so we have plenty of time to talk between sleeping and sailing.

Simple life at sea

I am feeling sad that our precious journey, a five-year circumnavigation of the world, is coming to an end. We have loved the simplicity of our adopted life style – the lack of material goods, the wholesomeness of our existence. I remember how complex our ‘old life’ was, the roaring hum of the city, the wasteful consumerism, the backstreet smells, the pressure of work, family and daily existence. I know I don’t want that back.

Now we sailed free, as fast or as slow as the weather will let us, make electricity from sun and wind and fresh water from the salt water of the sea. We catch fish, grow alfalfa, mung beans and herbs and to augment our ship’s supplies, and make bread every second day.

So I sit dreaming about how we might create a life on land similar to this life in the ocean. Five years cruising has changed both of us, and I want our future to be less wasteful, more caring of our environment.

Shipping containers

My husband and skipper Ted Nobbs is reading a book serenely when I say, suddenly, into the vastness of the ocean, ‘We could use old containers to build a house!’

Now Ted is an architect, so when one says the word ‘build’ or ‘house’ he is immediately alert.

‘Containers?’

‘Yes, old containers.’ I have heard of using containers for house building and I love the very outrageousness of the idea. ‘That would be very environmentally friendly.’

‘Mmmm’ he says, ‘Containers are hot-boxes you know, not very practical. They normally have to be airconditioned, not economical at all.’

Ted goes back to his book, no doubt thinking that would be the end of my flash of inspiration, but I am now on a roll, and my idea, my little dream of a very economical house made of containers, starts to take shape.

My plan

We’ll have three of them in a U shape, I think, with maybe a generous courtyard inside the U. I imagine a wide open space in the U, just glass walls and doors closing off the end. And a verandah around the lot – a big verandah, remembering my childhood in North Queensland. We’ll live somewhere green, I think, maybe on the Hawkesbury River.

I go to sleep into the snug warmth of the cabin,delighted with my creation. I am sure he must love it. But my delight doesn’t last much longer than the sleep. When Ted wakes me for my next watch, he sounds negative.

‘The weather is still fine, no ships, not even a bird going by. But that house of yours, you know, there are lots of issues trying to make a house from containers. Containers are only eight feet wide. How would you fit even double beds?’

I am just about to complain that architects are a stuffy conservative lot anyway who don’t like anything new, but he goes on: ‘But I like the basic idea. It would be a great challenge to create a house that is at the same time environmentally sound but elegantly so and based on ideas that were prevalent in the colonial days of Australia.’

Gradually Ted’s enthusiasm for his project overtakes mine. He creates solutions. He thinks of using refrigerated containers for better insulation, and as for the narrowness of the containers, ‘We’ll have a kind of bay window in the base of the U for the kitchen. ‘You can’t operate in an eight foot kitchen.’ It’s coming together nicely, until one day, when we are berthed in a marina in Fiji, he hands me a sketch, saying, ‘Well here it is, with your wide verandah. But you should know that using containers in the shape of a U means you will end up with a house of 500 square metres.’

‘What? No, no, no I wanted a SMALL house. There’s only two of us – living on the boat has been such a freedom – we don’t need a big house!’ ‘I know,’ he says, taking out another sheet of paper, ‘so here is my alternative.’ ‘You’ve been working on another whole plan all the time?’?’

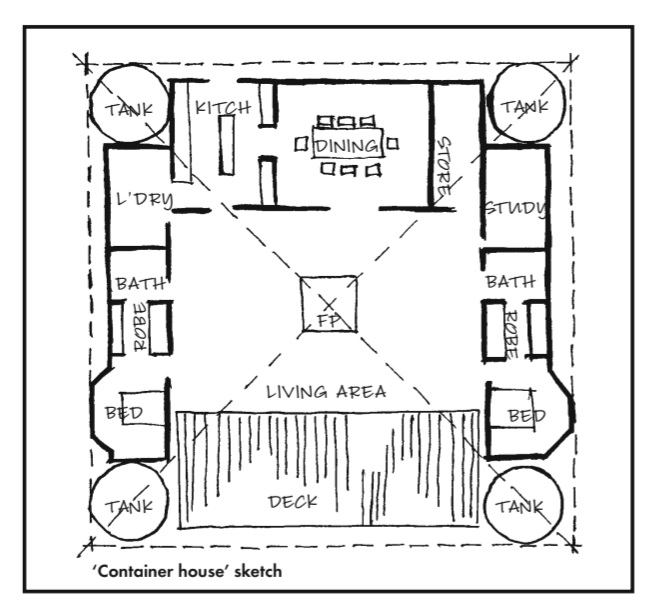

“Well, it’s a bit of a sketch of a different idea.” He hands me one of the sheets he has produced:

I stare at the sketch. ‘What’s this?’

‘An alternative, a small four bedroomed house.’

‘Four bedrooms! We don’t need four bedrooms! Two is enough!.’

‘Yeah, I thought you’d say that, so here is a more detailed one, with only two bedrooms – same house, but two studies instead of bedrooms.’ He hands me his second sheet of paper.

‘Wow, this is more detailed.’

‘Yup,’ he grins, ‘and it’s perfect, you’ll see, the most elegant and environmentally sound house that’s ever been built.’

I take the paper and stare at it.

‘No containers,’ I say miserably.

‘No containers. I am going to get some fuel for the dinghy. Study it while I am away.’

My precious containers are gone and I feel as though I have lost a friend – but I can still see some germs of ideas that had been mine – the big verandah, the tent fly idea, and, amazingly, the water tanks are still part of the house. But some things I can’t see.

‘Concrete?’ I bluster when he returns, pointing to the word on the sketch. ‘You want to make the whole house out of concrete?’

‘No, silly, just the floor,’ he explains, the roof will be corrugated iron, same as in the container house.’

‘Good, fine then. I love corrugated iron – we’ll feel good about that too – no trees cut down.’

‘Just the roof of course – the walls will be glass.’

‘Right … glass.’ I think about it.

‘How many walls will be glass?’

‘All of them.’

‘You can’t be serious.’

‘Sure I am, it’ll be wonderful, you’ll see.’

‘The bedrooms?’

‘Yup.’

‘The bathrooms?’ (How far could he go?)

‘Yes, the bathrooms too.’

‘Ted, you can’t have all the bedroom and bathroom walls made out of glass, and I’m not living in a house with all the bedrooms and bathrooms made of glass.’

‘Come on,’ says Ted sweetly, ‘you told me you wanted to live somewhere very green and leafy. There’ll be no-one looking in the windows, and we’ll have a great view while bathing.’

‘… and, because you might change your mind, it will be easily convertible back to four bedrooms.’

The architect’s plan

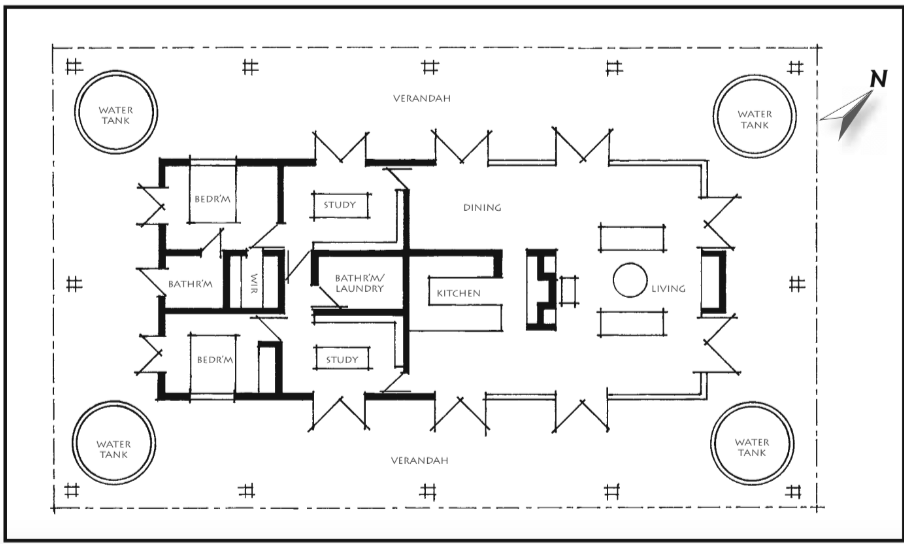

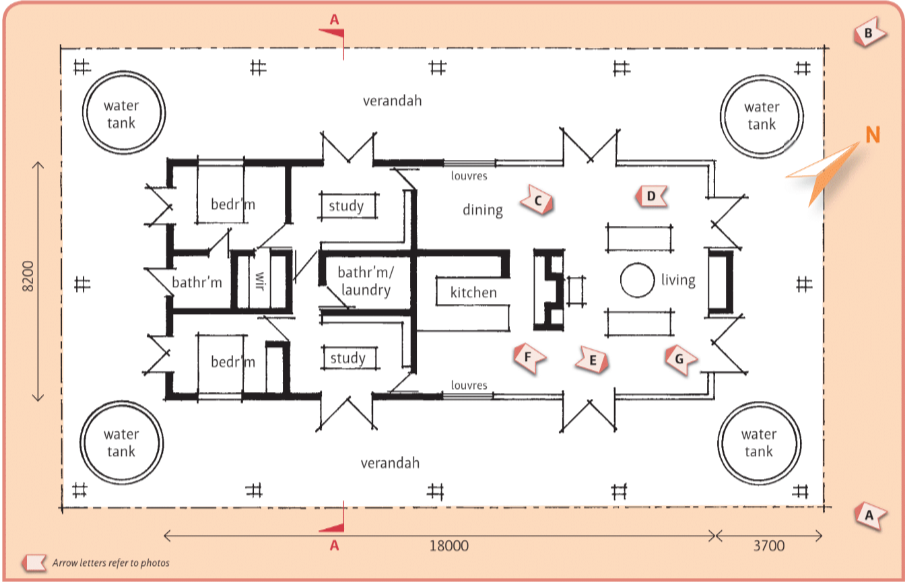

There are some things I really like. The house is simple, but curious. The kitchen is in the middle of the house, surrounded on three sides by living and dining areas. Beyond the kitchen are two bedrooms – which are now to become studies, symmetrically placed, with a general bathroom between. Then two more bedrooms, one of them with an ensuite and dressing room, the other, I guess, to be our guest bedroom – perfect.

Trying to be positive, I leave the question of a glass-walled house alone for a while.

‘I love the simplicity,’ I say, ‘and the big verandah. And I can see the tent fly is there. It will work, won’t it? I mean – we won’t need airconditioning?

Fly-roof ventilation

The colonists knew a thing or two about ventilation, and they couldn’t cover their mistakes by putting in air-conditioning. The fly-roof will keep the sun off the main roof, and the air-flow between them will remove the hot air.

This is one area of the house we haven’t discussed very thoroughly. Now it’s a reality, I start to think it through. ‘Well, that will happen in winter too, when we WANT the heat to reach us.’

There was no hesitation. ‘I’ve thought of that. In winter we’ll shut off the area between the fly-roof and the main roof so that the warm air is retained. You’ll see, it’ll be beautifully warm in winter.’

But I couldn’t see it. The house would still be colder than if the sun beat directly on the roof.

Architects can be very frustrating. They are good maybe at drawing, but not very clear about explanations. He goes on to describe a complex system of airflow so that the warmth from a pot bellied stove in the living area will be magically transported to the bedrooms by the force of the natural behaviour of different temperatures in the air.

I cannot imagine how I will ever be comfortable in this house with a concrete floor, corrugated iron roof and glass walls, But Ted’s delight is a pleasure to watch. On arrival in Australia we go searching for somewhere to live.

Finding the site

Our dreams of houses might be different, but we do share one identical dream. We know we do not want to live in Sydney where our friends and family are. But we can’t abandon them entirely, so we draw a three-hour ring around Australia’s largest city, and start searching. Giving up the idea of the Hawkesbury quite early, we roam the countryside south, west and then north. The first day we drive north of Maitland, into the cattle growing and dairying valleys which spread around the tributaries of the Hunter River, we are entranced.

The green valleys, the rich soil that has brought forth massive trees, the charm of the villages – Vacy, Paterson, Clarence Town, Gresford, Stroud and Dungog – is overwhelming. It takes us several months of searching, but finally we find what we are looking for – an empty 16 hectares just north of Dungog, high on a hill with a view of the surrounding hills, over the township of Dungog and on to the Barrington Tops.

While waiting for the plans to be approved and pass the BASIX requirements, we dig three dams, build roads, fences and a shed, burn the blady grass and chip out the thistles; but things are not going well.

BASIX problems

‘It’s unbelievable,’ complains Ted, ‘they don’t get it at all.’ He is talking about the authorities who must approve the plans.

‘If I had planned a McMansion, with no eaves and impossible to live in without air-conditioning, it would have passed BASIX without a problem. Because they don’t understand the airfl ow concept, it doesn’t pass.’

‘That’s ridiculous,’ I say loyally, ‘can’t you explain it to them?’

‘BASIX works by ticking the boxes.

There’s no box for natural air flows and they don’t seem to understand double roofs or ducted heat exchange.’

I had some sympathies with BASIX. I didn’t understand bathrooms with glass walls, and concrete floors in the living room. My old container concept had a nice timber floor in the living room and a wide timber deck around the outside.

When asked by friends I say, ‘Well, he’s the architect and I am the writer. He doesn’t interfere with my writing, so I guess I shouldn’t interfere with his architecture.’

‘But YOU have to live in the house too.’

‘I know, I know.’

But there is no stopping Ted’s passion for his ‘elegant, environmentally sustainable house based on our colonial past.’ He is on a mission and, to give him credit, he DOES finally make ‘them’ (if not me) understand, and the design of the house gradually becomes more detailed. He has even made provision for two more bedrooms if you want them as the walls are non-structural. (I don’t)

It IS the small house that I wanted, but I am not sure now about other things – even about the water tanks – they seemed to go with the containers, but I cannot imagine them on verandahs. The glass-walled bathroom doesn’t even bear mentioning.

So here I am, watching through the window on Day One of the construction. I wonder if Ted has any doubts like me, but this is no time to ask. He is out there in the soft morning air, as all owner builders should be, keeping one eye on the weather and watching the great crane pour litres and litres of liquid concrete onto our house pad.

Will his compelling dream work in practice? Will this be a superior, but less expensive home than many a kit home? Will I, as he promises, love this strange house?

Next phase – Published by Owner Builder Magazine Oct/Nov 2012 – A dream in the Making: Our Half Built Shedhouse

This record was published in Owner Builder Magazine, in the Oct-Nov 2012 Issue

Will it be a house? Will it be a barn? No it’s a SUPERSHED! (… or at least that’s the idea.) Four months have passed since my husband, architect Ted Nobbs, embarked on a mission to create the most beautiful and environmentally green shed/house on the planet and build it in the countryside near Dungog in New South Wales.

The dream, the concept, is a good one– to create a marvellous country dwelling with just four guiding principles.

It may have been a dream ride for Ted but just watching from the sidelines in the small shed where we are living while building, has been verging on the nightmarish for me – and we’re only half-way there! It’s constant chaos, with trucks and cranes arriving and leaving along with their attendant workmen and clouds of dust. Timber and iron and steel and boxes of nameless objects are delivered daily. Hammering and high pitched screaming of equipment fill the air and mask any hope of hearing the kookaburras. As a work-from-home journalist, my concentration skills are being well tested.

The Dream

1. Shed technology: Ted wanted to useshed technology to make the building economical and fast to build. The reason that shed technology is faster, very much faster, is that all the pieces come ready-made, meaning that erecting it is a little like playing Lego– or erecting DIY furniture from IKEA.Also, we were both happy to embrace one of the building materials so fundamental to Australian history –corrugated steel.

2. Going green: We both wanted to make the building – the shed – as ‘green’ as possible, a ‘smart’ building that would need little or no artificial heating or cooling. Situated in the cattle raising grasslands of the Hunter Valley, the area does suffer extremes of heat and cold, so the house – er, shed – would need to be cleverly designed. We would have solar panels for electricity and lots of water storage incorporated into the building. As escapees from the city this was an exciting prospect.

3. Modern interpretation of classic pioneering design: Ted wanted to incorporate some of the lessons learned from our pioneer forebears about ventilation. With no recourse to air-conditioning, they had to be ingenious. In far north Queensland there are houses with 3.5 metre wide verandahs and double roofs. The underroof, made of corrugated iron, kept out the rain. The outer roof, much larger than the main house and covering the wide verandahs, was made of natural thatch and acted like a tent fly, keeping the house cool in the highest of temperatures. So the goal was a modern interpretation of this classic design.

4. Simply beautiful: Finally, Ted wanted to make the most beautiful building in the world; simple, authentic and inclusive of the green bushland hills around us. That meant that most of the walls were to be glass.

But no matter how good the dreams are, it’s the practicalities that have to be overcome which keep the adrenaline flowing and one’s feet on the ground. I can’t tell how many times Ted has stormed into our small shed, praying. Well, I think he’s been praying. He has been saying ‘Jesus Christ’ and ‘God Almighty’ a lot, although there are some other words that I don’t rightly think should go in a prayer.

‘What’s the matter now?’ is my usual opening. From the resulting conversations,I can piece together the issues that have made life interesting in the building of this shed/house, so far.

Concrete slab:

Much thought had been given to whether the floor was to be of timber or concrete, but as we were building in the country, we decided on concrete. This was firstly because of its practicality and hardwearing nature, and secondly because rabbits, snakes and runaway dogs cannot burrow or nest below the floor.

We chose a clay colour, curiously called ‘pumpkin’ in the swatches, because the colour matched the local rocks. The verandahs are imperceptibly sloped outwards for rain run-off purposes, except in each corner,where the water tanks are to sit like bookends to the verandahs. Naturally,these sections had to be flat. The team achieved a good result, with colour consistency and a surface that will require very little grinding to achieve the final polished appearance.This part of the build was achieved with great nervousness, as a mistake with a concrete slab is very difficult to correct,if it can be done at all. There was a lot of praying going on during that time. After allowing the concrete to cure for two weeks, regularly spraying with water to complement the incessant rain, Ted was able to start preparing for the erection of the steel structure.

Shed technology:

Now one of the truly charming things about shed technology is the order of building. ‘Normal’ house construction begins from the ground up, and it is not until sufficient walls are built that the roof can be attached. So there’s always one eye on the weather during this period, and a long run of inclement weather can spell disaster for programmed works. Not so with a shed.

The skeleton structure is erected, a couple of days work, and then the roof is next, another couple of days work and all subsequent construction work is performed under cover. Timber framing and all subsequent work was able to be erected underneath in dry and stable conditions, with no loss of time during what turned out to be one of the wettest summers for the area in local history.

It was while all this was going on that Ted seemed to be praying the most. Mobile glued to ear he was obtaining prices: forwindows, for plumbing fittings, for kitchen fittings and many ancillary items, and negotiating to ensure the program for the commencement for the plumbing works and electrical works. To listen in (and this was sometimes difficult to avoid) you’d think it was a new Empire State Building he was erecting. However, by some super smart timing and coordination,the roughing for the plumbing and the electrical was done simultaneously and was completed in three days.

Natural convection

Part of the process of ‘going green’ is to use as little power as possible while staying cool in summer and snug in winter. So it is the hot and cold air transfer system using natural convection principles that I find most exciting about the design of our future shed home. Sadly for him, Ted eventually had to reduce the area of glass in the building because sucha use of natural airflow currents is outside the realm of BASIX calculations, which uses a very structured method to ensure a building environment is adequate.

The argument was that so much glass did not allow adequate insulation. Until the house is actually built, he can’t prove the system works, but to build it he must first comply. A classic catch-22. Fundamental to the concept is the house design. The basic ceiling line of the house follows the 22 degree pitch of the roofs (making a cathedral effect) except in the central area where the two bathrooms and kitchen are lined up along the apex of the roof. Here we have a 2400mm ceiling/under-roof above which, to the underside of the inner structure is a two metre wide by 1.5 metre high services corridor in which all of the heat transfer ducting, water pipes and electrical cables are located. Because the corridor is so spacious it will allow ease of maintenance and/or addition, should it ever be required.

Above the slow combustion stove inthe living room is an intake louvre, inside which, near the entrance, is a small fan. This fan takes the hot air from the ceiling space, and directs it along the ducting pipes to enter via outlets into the two studies and the two bedrooms, thus pushing the cold air from these, which is (because of the air being removed from the living room’s upper spaces) sucked into the living room. In this way the warm air will be circulated throughout the house. The design intent is that the fan will be turned off after a short period of time as a natural convection current will be set up.

As Dungog has been known to achieve temperatures during summer extremes of 45–46 degrees for two weeks constantly, we have decided to install air-conditioning for these times, and have used the same ducting and air transfer system to manage the cooling of the house. Based on our current experience, we don’t believe that it will be necessary to use this very often.

But there is another factor to the natural convection system. The outer and inner roofs are separated by one metre of air space, and the gap on the perimeter is enclosed with four two-metre long louvre systems on each side. This is a direct copy of the system much used during our pioneering past, as the louvres are open during the summer to allow airflow

However, in a sophistication of the original system, shutting these louvres during the winter will trap warm air and create insulation from the cold. The house has been oriented to capture the prevailing breeze that comes down the valley and over the saddle from the sea. This breeze arrives every day, just prior to sunset, and was (along with the view) one of the basic criteria for the siting and orientation of the house.

Glass walls

The original design, which involved all glass walls, had to be modified to comply with BASIX, but for such a small house (without the verandahs it is a mere 144m2), it is still largely glass-walled. The two bedrooms now have opaque walls, I am happy to say, never having been happy with the idea of sleeping with the cattle watching, but they nevertheless have very large picture windows and large glass double doors. The front of the house has a wide view over the town of Dungog to the Barrington Tops and this is completely glassed and open to the view. There are double glass doors which open onto the 3.5 metre wide verandah which surrounds the house, several plain glass walls and two floor-to-ceiling glass louvre panels. The glass is not double glazed, but are made instead of Smart Glass, which assists in the prevention of heat transfer. The windows, walls and doors are now installed, and the corrugated steel cladding has commenced, after which we shall complete the insulation and linings then painting and fitting out.

Difficulties so far

Contractors:

Using contractors in the country has its upsides and its downsides. Ted has enjoyed working with the straightforward, ethical but easy-going culture of the countryside. Unlike similar contractors in the city, these are all small firms, run by men with families who live in the surrounding areas. They are pleasant, accommodating and always ready for a chat or to give some heartfelt advice to the new city ‘blow-ins.’The disadvantage is that, because they are small firms, a delay on one job caused perhaps by weather or the late finishing of another contractor, can ruin their scheduled starting date. Larger city firms are able to juggle much more successfully. This has meant that Ted has been forced to be patient at times (a very difficult thing to ask of a passionate planner) and wait for contractors to turn up, sometimes many days after their promised start date. This has been the most serious cause of delay in the building.

Budget:

One of the difficulties of being an owner builder in the country is maintaining budget, because of the difference between realities and early discussion with suppliers and the final quoted figure for a particular element.There have been many instances of establishing with suppliers and contractors budgets for desired finishes that on receiving the final price necessitated changes and use of alternative materials, due to price increases of 20 – 25% above the initially discussed budget. While this has been a frustration, there have also been some pleasant surprises too, with suppliers coming back with lower figures than early discussions.

Now the shed is starting to look like a house, the prospect of finishing it and moving in is very exciting. Will it work as planned? My architect says it will and I go to sleep every night hoping he is right and that the chaos will end soon.

Watch this space…

Published by Owner Builder Magazine Oct/Nov 2013

The new best idea in building, the Shedhouse – A final update

‘It will work, it’s clear science that it will work.’

‘Well, what if it doesn’t?’

Pause. Ted, my husband, seems to take a breath.

‘We’ll move!’

‘No, we won’t! If we are building our unusual building-thing to live in in the country, we’re going to live in it, come what may.”

‘Why don’t you call it our home? That’s what we are building.’

‘Because it’s not a home, it’s a shed. I still can’t imagine inviting people for dinner. Can you imaging: “Hi darling, Please come over to my shed on Friday night for dinner”.’

He can’t resist a chuckle.

‘Don’t worry about the heating, I promise you it will work.’

I flump off, not satisfied.

But when I walk around my house now it’s not the interminable ‘conversations’ that Ted and I had during the construction that I remember. What I remember is the original dream – the dream of simple living that we so much take for granted these days. When I say ‘walk’ I often feel as though I am floating, and when I say ‘house’ I do really mean ‘shed.’

‘That heating system would never work! We’re going to freeze in winter.’

The dream

Because, you see, sailing across the Pacific Ocean at the end of a delicious six-year experience, my husband and architect Ted Nobbs and I dared to dream of something we didn’t really know would be possible; a house as simple as our life on the sea – as simple as the life-style of the Pacific Islanders we were seeing every week in our grand trek across the ocean. We have it now, the shed and the dream. Yes, we live in a shed, and apart from our telephones, we are independent of the rest of the world for water, power, even food, if we concentrate on the vegetable garden. It gives me non-rational and unexpected rushes of joy that we make four times as much pure clean electricity as we use, that we are a nett contributor to global cooling.

Shed technology

One friend visited and said, with admirable honesty, staring at the steel columns of the verandah and the corrugated iron walls, ‘Well… it’s not my cup of tea!’

But it IS ours, and that’s the important thing.

Others visit and say, ‘But it doesn’t look like a shed.’ And they are wrong too. Because it’s shed technology; made of concrete and corrugated iron, of glass and steel, and will last almost forever. Inside, of course, we have spread it with soft Turkish kilims and a rumple of cushions and covered the walls with hangings and paintings.

THAT’s why they say ‘it doesn’t look like a shed.’ Just outside the walls, which are mostly glass so the natural world can enter, there is a 3.6m verandah on every side of the house. (In fact the verandah is larger than the house – 156m2ofverandah vs.144m2of house) We love verandah living, so it is spread with cane lounging chairs, a rocking chair or two, a hammock and plenty of tables so we can pick the best weather for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Actually, the wide verandah finds us there often eating while it’s raining. But of course there’s much more to our shed-house than my delight in living somewhere I love. Ted has created an environmentally sound, natural building, based on our colonial past.

Heating and cooling

There is a fly-roof that sits a metre above the normal house-roof. In summer the breezes flow between the roofs, removing any generated hot air, and keeping the sun’s heat far away from our ceiling. It’s as if the house has an umbrella to stay cool all summer.

Conversely, the louvres which join the two roofs are shut in winter to keep the hot air enclosed. The idea stems from the early colonial farmhouses of North Queensland, in the days when they couldn’t resort to air-conditioning. As I write, it is winter. When our natural convection heating specialists advised us how to make a small slow combustion stove warm the whole shed-house, I can admit now I didn’t believe them or Ted when he saw the light and decided to build it that way. I had lived in houses with wood-burning fireplaces –the room you were in was warm, but you had to turn the electric blanket on early and scoot through the freezing air of all the other rooms to get to the bedroom. Good for cuddling your partner, but miserable in the main.

I have to believe them now, because the entire house is warm – hardly a degree difference between the living room where the slow combustion stove is located and the other end of the house. Itis as if we have air conditioning, but the warmth is all generated from the stove. How did they do it? Natural convection, with a little help from a small fan, is an amazing thing. The air rises into our cathedral ceiling, the fan sucks it into a large duct that courses through the apex of the building, spurting out hot air into every room. As the warm air spurts into each room, that drives the coldest air (always near the floor) into the vacant space left by the departure of the warm air. So a small current is set up, which successfully rotates the air around the house. You can’t feel the current, it’s so slight, but, as if by magic, the air in the house (in our case, shed-house) is uniformly warm. Yes, it works! And it’s cheap. Just for the price of the wood for the small, but very efficient pot-bellied stove, we can warm the whole house, even in the coldest temperatures.

Letting the natural world in:

But back to ‘floating’, when I am really only walking. Why is that? Why do I have such a feeling of floating? I have worked it out that it’s because of the way in which the birds, and the grasses, the trees and their waving leaves seem to be with me as I walk. Why do we have closed-inwalls in our houses – oh, for privacy you say? Well, I can understand that in the bathroom, but in every room? Now I have become passionate about the effect of letting the natural world into your house. Be it a garden, a grassland, a forest view or merely a courtyard of vines and flowers, let it enter your house, so that you will not feel alienated from our natural world. The floor in this shed is polished concrete – very hardy, very attractive ‘pumpkin’ is the colour – a sort of clay shade. On the verandah it has been left with a rough pattern, so it won’t be slippery when wet. The cathedral ceiling inside is pine timber, the walls are plasterboard (just like a ‘real’ house) and outside on the verandah the walls are, yes, grey Colorbond corrugated iron. It’s very hardy – almost nothing is trashable.

So, in spite of all my preconceptions, doubts, misgivings, disturbed nights awake and interesting ‘discussions’ with Ted, this shed-house is perfect. It’s environmentally friendly, it’s marvellous to live in and I think this one even looks nice.

Leave a comment